Don't start from the good old things but the bad new ones. Bertolt Brecht

I want to begin with the moment when the strategy of accelerating through and beyond capitalism was first explicitly theorized. This took place in France in the early to mid-1970s with three books, each appropriately trying to outdo and out-accelerate the other in the attempt to give this strategy its most provocative form. It is these works that frame the debate concerning acceleration and which probe the tense relation between strategies of acceleration and the solvent forces of capitalism.

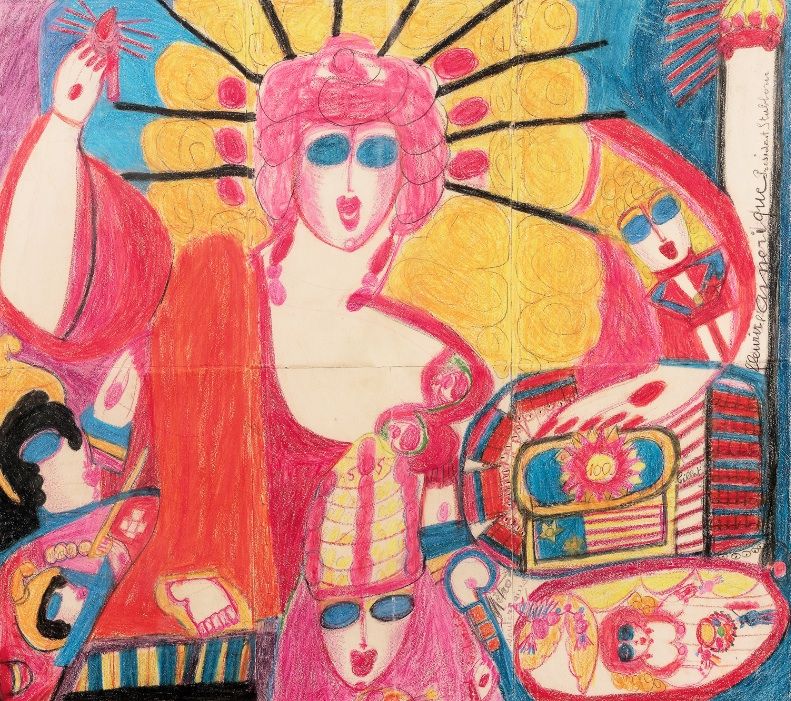

The first is Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), which, as its title suggests, was devoted to a scathing critique of psychoanalysis for confining the force of desire within the Oedipal grid. The ambitions of the book, as its subtitle indicates, went far beyond this. Deleuze and Guattari reevaluated schizophrenia as the signature disorder of contemporary capitalism, arguing that the breakdowns of the schizophrenic were failed attempts to break through the limits of capitalism. Capitalism was unique for unleashing the forces of deterritorialization and decoding that other social forms tried to constrain and code. This release was, however, always provisional on a reterritorialization that dragged desire back into the family and the Oedipal matrix, recoding what it had decoded.

Deleuze and Guattari's strategy for revolution was posed in a series of rhetorical questions:

But what is the revolutionary path? Is there one? – To withdraw from the world market, as Samir Amin advises Third World Countries to do, in a curious revival of the fascist 'economic solution'? Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go further still, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not yet deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough, from the viewpoint of a theory and practice of a highly schizophrenic character. Not to withdraw from the process, but to go further, to 'accelerate the process', as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven't seen anything yet.

[…] In reply, Jean-Francois Lyotard argued that Deleuze and Guattari hadn't gone far enough. Their celebration of desire still supposed that it formed some kind of exterior force that capitalism was parasitical to, and which we could turn to as an alternative. Instead, Lyotard's Libidinal Economy (1974) insisted there was only one libidinal economy: the libidinal economy of capitalism itself. We cannot find an 'innocent' schizo desire, but instead have only the desire of capitalism to work with. In what is perhaps the most notorious accelerationist statement of all Lyotard did not shy away from the implications of his position:

the English unemployed did not have to become workers to survive, they – hang on tight and spit on me – enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion it was of hanging on in the mines, in the foundries, in the factories, in hell, they enjoyed it, enjoyed the mad destruction of their organic body which was indeed imposed upon them, they enjoyed the decomposition of their personal identity, the identity that the peasant tradition had constructed for them, enjoyed the dissolutions of their families and villages, and enjoyed the new monstrous anonymity of the suburbs and the pubs in morning and evening.

Lyotard denies the kind of left politics that would insist that the worker suffers alienation in their separation from their community, their body, and the organic. Instead Lyotard suggests that the worker experiences jouissance, a masochistic pleasure, in the imposed 'mad destruction' of their body. Unsurprisingly, Lyotard's remark lost him most of his friends on the left, and even he would later refer to Libidinal Economy as his 'evil book'.

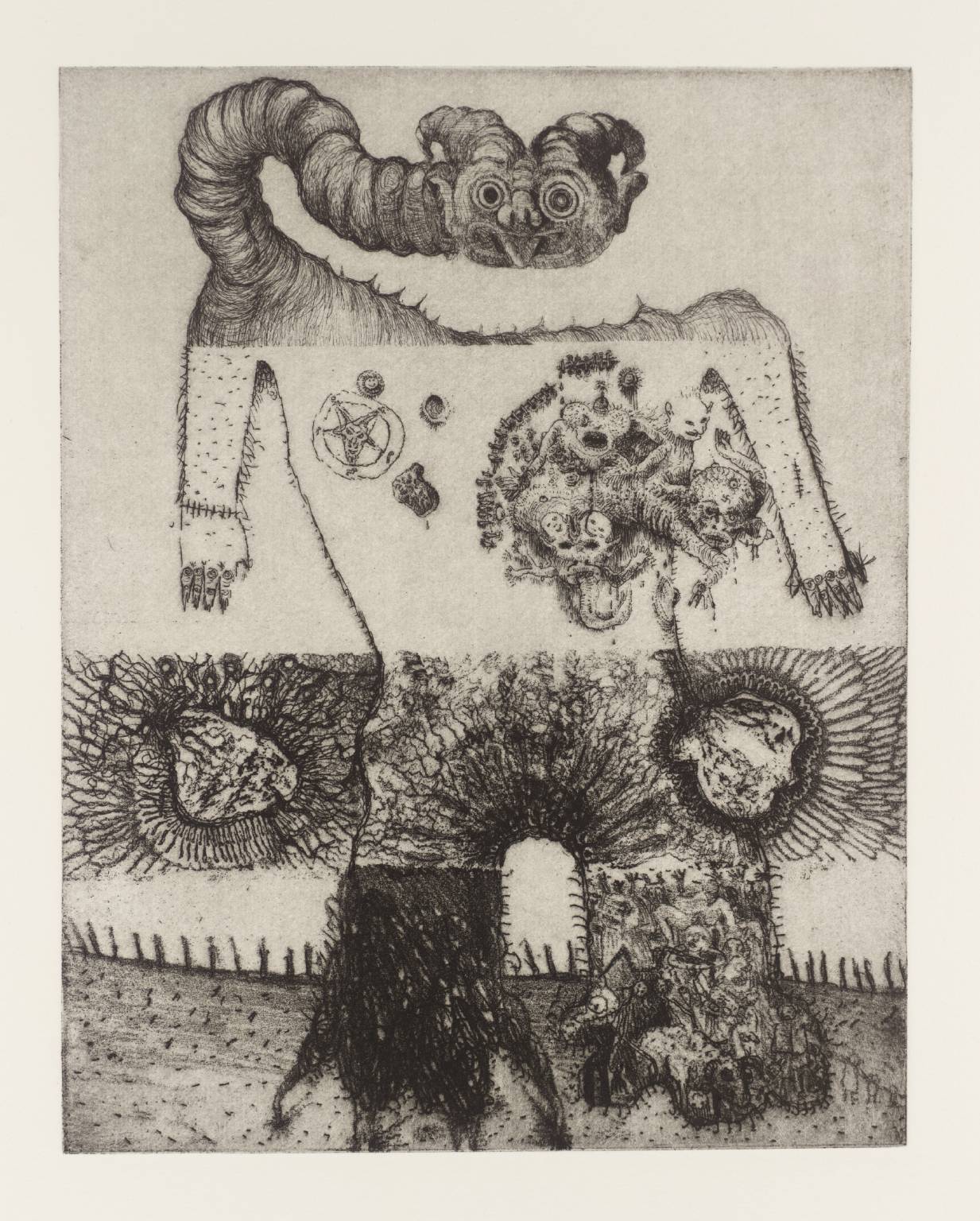

[…] Jean Baudrillard's Symbolic Exchange and Death (1976) would criticize both Lyotard and Deleuze and Guattari for their nostalgic attachment to desire and the libidinal as oppositional forces. Only 'death, and death alone' incarnated a reversible function that could overturn the omnivorous coding capitalism imposed. What Baudrillard found in death was a 'symbolic' challenge that exterminated value by returning to a pre-capitalist economy of the gift, which was now linked to exceeding the forces of capital by 'magical' reversal.

Baudrillard, however, takes a distance from accelerationism by disputing the metaphysics of production that underlay Marxism and these dissident currents. In The Mirror of Production (1973) he had already critiqued 'an unbridled romanticism of productivity'. For Baudrillard what accelerated was not some force of libidinal flux or flow, but a catstrophic and entropic negativity that floods back into the system causing it to implode – the result is a terminal accelerationism.

[…] In this dizzying theoretical spiral we can see a common accusation: each accuses the other of not really accepting that they are fully immersed in capital and trying to hold on to a point of escape: desire, libido, death. Each also embodies a particular moment of capital: production, credit, and inflation. The result is that each intensifies a politics of radical immanence, of immersion in capital to the point where any way to distinguish a radical strategy from the strategy of capital seems to disappear completely.

In Joseph Conrad's novel Lord Jim (1900), the character Stein gives some (for Conrad) characteristically enigmatic advice:

A man that is born falls into a dream like a man who falls into the sea. If he tries to climb out into the air as inexperienced people endeavour to do, he drowns – nicht wahr? … No! I tell you! The way is to the destructive element submit yourself, and with the exertions of your hands and feet in the water make the deep, deep sea keep you up. So if you ask me – how to be?

His answer: 'In the destructive element immerse'. These theoretical accelerationists take Stein's advice to heart. We fall into capitalism and, rather than try to climb out, we have to submit and swim with the capitalist current.

This reaction could be seen as a result of the defeat of the hopes inspired by the revolutionary events in France, which are condensed in the signifier 'May '68'. At the time Deleuze and Guattari, Lyotard, and Baudrillard were writing this defeat was not evident, and many others were working throughout the 1970s to sustain and radicalize the sturggles unleashed in '68. Those energies would fade into the reactionary 1980s, and then the accelerationist positions of Deleuze and Guattari, Lyotard, and Baudrillard would become prescient. Their positions registered the durability of capitalism and its ability to spread its domination, often by recuperating forms of struggle. The totalizing effects of capital would appear capable of rolling-up revolutionary advance, making the search for a revolutionary subject outside of capital superfluous. While Deleuze and Guattari would maintain faith in new revolutionary subjectivities – the 'schizo', and what they would later call 'minor' becomings – Lyotard and Baudrillard would more firmly embrace disenchantment.

Far from simply being signs of the times these accelerationist formulations gained resonance as predications of the bad days to come. They would find more purchase in the 'polar night' of the 1980s. At that point rising fears of nuclear destruction, a glaciated Cold War, and the beginnins of the neoliberal counteroffensive, offered a felt experience of closed, if not terminal, horizons. Being a teenager at that time was to live in an atmosphere of ambient dread, summed-up for me in viewing the traumatic BBC post nuclear-attack film Threads (1984) and the paranoia of Troy Kennedy Martin's Edge of Darkness (1985). It has recently been revealed that Whitehall planners had formulated a nuclear war-game scenario with the suitably chilling codename Winter-Cimex 83. My later reading of Baudrillard's In the Shadow of the Silent Majorities, published in the Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents series of little black-books, produced an immediate sense of recognition in this mood. Baudrillard's implosive theorization would be truer to the inertial nature of capitalism, disputing accelerationist images of ever-expensive capitalism.

The reason theoretical accelerationism caught this mood was precsiely because it was formulated in the mid-1970s, at the beginning of the long capitalist downturn. These hymns to the excessive powers of capitalism were articulated in the face of crisis – the 'oil crisis', the abandonment of the gold standard, and the crisis of productivity, as well as the political crisis of legitimation (Watergate, etc.). In 1972 the Club of Rome published The Limits to Growth, which used computer modelling to argue that capitalism was undermining the material bases of its own 'success'. So, in a strange way this theoretical moment of accelerationism seemed to be running against the current of capitalism entering a period of stagnation, deceleration, and decline. On the other hand, however, it appeared predictive of the sudden 'acceleration' of cybernetic and financial forces that would form the basis for neoliberalism, signalled by the election of Margaret Thatcher in the UK in 1979 and the election of Ronald Reagan in the US in 1980. The fact that, in particular, Deleuze and Guattari's term 'deterritorialization' would find a fecund future in being used to describe neoliberal capital is one sign of this.

These models formulate, in advance, the common sense of the '90s that 'there is no alternative' (TINA). If we follow the career of accelerationism across these moments we see it engaging and reengaging with the closing of the horizon of capitalism. It offers a way of understanding the continuing penetration of capitalism – horizontally, across the world and vertically, down into the very pores of life – and alos, of celebrating this as the imminent sign of transcendence and victory. Our immersion in immanence is required to speed the process to the moment of transcendence as threshold. In this way immanence is paired with a (deferred) transcendence and defeat is turned into victory. At the same time defeat is registered by these forms of theoretical accelerationism in the form of ecstatic suffering, of jouissance, experienced in our deepening immersion.

This theoretical moment involved a strange fusion of Marx and Nietzsche. It took from Nietzsche the apocalyptic desire to 'break the world in two', and the need to push through to complete the nihilism, the collapse of values, that afflicts our culture. Nietzsche did not decry the collapse of values, but saw these ruins as the possibility to move beyond the limits of Western culture.

This would be fused with Marx's contention that history advanced by the bad side, which welcomed the solvent effects of capitalism in dissolving the old world. The result was a Nietzschean Marx, a Marx of force and destruction. In 1859 we find Marx hymning the productive powers of force:

No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.

In this modelling we have a teleology – the linear passage through different modes of production in which communism solves the riddle of history and promises a superior mode of productivity, one not subject to the antagonism of capitalism.

Perhaps the most controversial moment of the 'Nietzschean Marx' is the series of articles he wrote on India. In his 1853 article 'The Future Results of the British Rule in India' Marx stressed how British colonialism would disrupt the 'stagnation' of India and appears to welcome the violence of colonialism, the arrival of industry, and the railways, as a necessary shattering of the old ways. Even this is, however, equivocal. Marx notes that bourgeois 'progress' always involves 'dragging individuals and peoples through blood and dirt', and that British colonialism has hardly brought anything beyond destruction. For Marx it would only be through social revolution that these 'developments' could be appropriated to forge a just society.

While there is a teleological Marx of development and production, Marx also insisted that capitalism does not automatically lead to communism. In The Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels argued that capitalist crisis posed the choice between the 'common ruin of the contending classes' and 'the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large'. Marx welcomed worker struggles to reduce the working day and to struggle against the despotism of the factory; he did not argue that it would be better if factory conditions got worse so workers would be forced into revolt. The fact that history advances by the bad side does not mean we should celebrate the 'bad side', but rather recognize this is the ground on which we struggle, which must be negated to constitute a new and just social order.

The theoretical accelerationists try to break this dialectic of redemption by emphasizing only the violent moment of creative destruction. In place of the just society generated through struggle, it is acceleration that becomes the vehicle of disenchanted redemption. This makes them heretics of Marx. While the classic theoretical accelerationists often adopt Nietzschean themes of contingency and chance, in terms of accleration they tend to reinstate the most teleological forms of Marxism. To resolve this problem accelerationism projects contingency on to capitalism, which becomes an anti-teleological, or 'acephalic' (headless) social form. In making this projection the accelerationists take as fact capitalism's fundamental fantasy of self-engendering productino. They are an archetypal instance of the fetishists of capital.

Certainly such a fantasy of self-engendering production is present in Marx, as we have seen. I think that the critique of this fantasy is a fundamental necessity. While we can certainly only begin to construct a just society on the ground of what exists this does not entail accepting all that exists or accepting what exists as it is given. This is a crucial political question: how can we create change out of the 'bad new' without replicating it? Of course, the accelerationist answer is by replicating more because replication will lead to the 'implosion' of capital. Replication, however, reinforces the dominance of capitalism, leaving us within capital as the unsurpassable horizon of our time.

It might be easy to dismiss theoretical accelerationism as a malady of those who take theory too far, spinning-off into abstract speculation. In fact, the very point of accelerationism is going too far, and the revelling and enjoyment engendered by this immersion and excess. They push into the domain of abstraction and speculation which, with the financial crisis, is evidently the space of our existence. I am sceptical that such a 'road of excess' will, in William Blake's words, lead 'to the palace of wisdom'. It does, however, lead us to think what this excess and abstraction might register. If accelerationism is not the revolutionary path it may be the path records, in exaggerated and hyperbolic form, some of the seismic shifts of capitalist accumulation from the 1970s to the president.

What accelerationism registers in particular are two contradictory trendlines: the first is that of the real deceleration of capitalism, in terms of a declining rate of return on capital investment, which has led to a massive switching into debt. The second is the acceleration of financialization, driven by the new computing and cybernetic technologies, which themselves create an image of dynamism. Of course, this 'contradiction' of deceleration and acceleration speaks to a dual dynamic as capitalism tries to restart processes of accumulation by accleration. The financial crisis that began in 2008 brought this contradiction to the point of collapse.

It is in this double dynamic that accelerationism finds its theorization, answering deceleration with the promise of a new acceleration, driven by faith in new productive forces that come online and disrupt the ideological humanism that tends to be capitalism's default ideology. In capitalism we are treated as free agents, although always free to choose within the terms set by the market. Accelerationists reject this 'humanism' by embracing dehumanization. They take utterly seriously the Marxist argument concerning the dehumanizing aspects of capitalism and they also take seriously those ideologues of the market who try to dehumanize us into 'mere' market-machines. This accounts for the instability of accelerationism, which is poised on this faultline.

It also speaks to the position of labor within capitalism: at once necessary, as Marx noted, to the production of value, while also constantly squeezed out by machines and unemployment. For Marx capitalism is 'the moving contradiction', which 'presses to reduce labor time to a minimum, while it posits labor time, on the other side, as sole measure and source of wealth'. This contradiction has only become more and more striking over the last forty or so years. The place of labor has shifted, at least in countries like the UK and US, from manufacturing to the so-called service economy (although this shift should not be overstated). It has also been displaced geographically and displaced in form – dispersed beyond the concentrated forms that it once held, or seemed to hold. At the same time, many of us work longer and harder. The relief that technology was supposed to bring from labor merely leaves less labor doing more work. No longer, as in Marx's day, are we all chained to factory machines, but now some of us carry our chains around with us, in the form of laptops and phones.

My suggestion is that accelerationism tries to reengage with the problem of labor as this impossible and masochistic experience by reintegrating labor into the machine. In what follows, we will see this fantasy of integration, the 'man-machine' (note the gendering), that might at once save and transcend the laboring body. This will take various forms, at once radically dystopian and radically utopian. Rather than taking this as a solution, I will argue it is a sympton. If we take accelerationism critically then we can use it to gauge the mutations of labor and its resistance to integration within capitalism and the machine – including sabotage, strikes, and more enigmatic forms of passive resistance. The stress of theoretical accelerationism on our immersion in capitalism will prove central to unlocking the various cultural and historical moments I will trace in this book. It is the extremity of accelerationism makes it the most useful diagnostic tool. It will also allow us to try and break the appeal of acceleration.

Source